New training initiative empowers officers across Canada to identify high risk threats to children

By Mara Shaw

Specialized training and data mining model rollout across the country, helping officers to recognize signs of child trafficking and sexual exploitation.

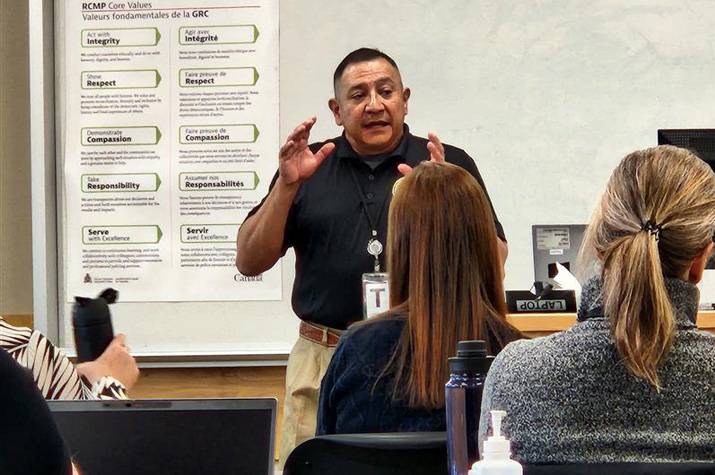

Image by RCMP

May 23, 2025

Content

A new initiative designed to enhance officers' ability to identify child sexual exploitation and trafficking is rolling out across the country.

The new course trains officers to recognize subtle signs of human trafficking, sexual exploitation and abduction. By teaching frontline officers to use a victim-centred approach, the team at Sensitive and Specialized Investigative Services (SSIS), an RCMP Specialized Policing Services program, hopes the training, along with a comprehensive data collection model, will help combat trafficking and child sexual exploitation.

Frank Barfuss, manager of the Criminal Intelligence Unit within SSIS's Behavioural Sciences Investigative Services says the idea to develop the program sparked while attending a Crimes Against Children conference in Dallas, Texas. There, he was inspired by a presentation by the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) on their Interdiction for the Protection of Children (IPC) initiative, covering its success in the U.S. After almost two years working in close partnership, and training with Texas DPS, the IPC North program was born.

IPC North places strong emphasis on intelligence sharing, cross-agency collaboration, and victim-centred policing. The program also draws on concepts of the well-known Pipeline Convoy course, that teaches officers to spot indicators of drug use or smuggling.

"The RCMP Pipeline course has been very successful," says Barfuss. "The IPC North program has been designed around the same principles, but you're looking at the traffic stop through a different lens—a vulnerable population lens."

Frontline first

While the Texas program serves as the foundation, Barfuss worked alongside team members like RCMP Sergeant Susan Shaw-Davis from SSIS's National Center for Missing Persons and Unidentified Remains, to frame the program around Canadian laws. Shaw-Davis, who holds a law degree and has gone on to become a certified IPC North trainer herself, understands firsthand why this training lens is crucial for frontline officers. "Our priority is frontline. They are the ones that have face-to-face contact with the victims and offenders," asserts Shaw-Davis. "We need to give them the tools to combat child trafficking, exploitation or abductions."

In a grassroots approach, Shaw-Davis parsed through lists of officers belonging to traffic units as key prospects for the program. "I worked frontline, and I know those officers—they care. There are a lot of passionate, dedicated people in traffic sections who, with the right tools, can have a massive impact in protecting the most vulnerable. IPC North is about providing those tools to support them in that work."

The training is delivered in two phases: a two-day foundational course for frontline officers, and a more comprehensive three-day training, equipping officers who've completed the first phase of learning with certification to teach others across the country. So far, 59 officers and civilians have completed the foundational course and 12 have been certified to teach. These trainers, drawn from areas across the RCMP including victim services, investigations, and traffic patrol units, will lead implementation efforts in their home divisions.

The program is especially relevant for the organization's traffic units echoes Barfuss, as they are most likely to encounter a broad spectrum of potentially harmful activity.

"We received a report from an officer who encountered an individual loitering in a school parking lot at 2:30 a.m. In the front seat of the car there were two barbie dolls tied up," recalls Barfuss. "So, is that illegal? No, but in terms of behavioural indicators, that's a huge red flag."

Detecting crime trends

At the core of this initiative is the first-of-its-kind Canadian fusion centre, which will collect data from traffic stops and cross-reference with information from internal RCMP investigation databases as well as external agencies, like the FBI and other local police groups. This component of the training builds a digital knowledge base for officers to submit suspicious activity reports, access resources and participate in continued training sessions on specific topics.

The fusion centre is strategically connected to a range of programs and services both within and outside the RCMP to share intelligence and develop new indicators. "These suspicious activity reports are intelligence-based. At the fusion centre we'll work to see if we can identify trends, geographic patterns, persons of interest, or other identifiers," says Barfuss.

Kristin Duval, manager of SSIS's Program Research and Development Unit within the Strategic and Operational Services unit, steered the development of the fusion centre, which she calls a "one-stop-shop."

"Technology has really facilitated the sharing of information, helping our officers access anything related to IPC North at their fingertips," says Duval. Interventions like electronic form submissions help to eliminate some of the administrative barriers that officers face. "Hopefully this system makes it easier, so officers can continue to do the important work that they're doing on the front line."

Building momentum

The biggest hurdles that remain are building awareness around the training, and establishing international partnerships, particularly those with U.S. law enforcement. But the integrated team steering IPC North is confident that the enthusiasm they've observed is only just beginning to build.

"The course has really taken off. There's strong interest, which is a little bit contagious," remarks Shaw-Davis.

She says one of the biggest mindset shifts participants took away from the training was the idea of slowing down during police interactions and using a victim-centred approach.

"The training prompts officers to slow down and ask more questions. Hopefully we can change some of the narratives police officers can have with people who are vulnerable, ultimately helping to protect more kids."