Hate crimes and incidents in Canada: Facts trends and information for frontline police officers

Note

This document was developed by the Strategic Policy and Transformation sector, under the leadership of Dr. Sara Thompson, a recognized subject matter expert and professor at Toronto Metropolitan University while on contract with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). The document benefited from the contributions and support of internal subject matter experts and members of the Hate Crimes Task Force, which is co-chaired by the Canadian Race Relations Foundation.

The information was originally compiled in 2023 and was updated in 2025 and will continue to be updated on a regular basis.

Please note that the RCMP has no affiliation with any media outlet, non-governmental organization, academic paper or research, website, reports or journalistic investigation, that may be referenced throughout this document. All media articles and research references throughout this repository are provided for illustrative purposes only and do not explicitly reflect the views of the RCMP.

The information compiled for this repository includes data up to the 2024 calendar year. New data sets, if available, can be viewed on Statistics Canada’s Police-reported Information Hub.

On this page

- Hate crime: concepts/definitions

- Hate crime and the Criminal Code

- Hate crime in Canada: patterns and trends

- Hate crime victimization: targeted groups

- Hate groups in Canada

- Hate speech and freedom of expression in Canada

- Hate crimes and incidents: victim/community reporting and why it matters

- The impacts of hate on victims, communities and society

- Victimization, trauma and the importance of a victim-centred police response: fact sheet and glossary of terms

- Hate crime victim support: a critical aspect of the police response and types of support victims need and want

- Cyberhate: fact sheet

- Is there a relationship between hate crime and violent extremism?

- Hate crime prevention: an important complement and supplement to reactive, enforcement-based approaches

- References

Copyright information

Hate Crimes and Incidents in Canada: Facts, Trends and Information for Frontline Police Officers

© His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, as represented by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 2025

- ISSN 2818-3096

- Catalogue number PS61-56E-PDF

List of acronyms and abbreviations

- 2SLGBTQIA+

- Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, assexual plus

- ADL

- Anti-Defamation League

- AG

- Attorney General

- CACP

- Canadian Association of Chiefs of police

- CSIS

- Canadian Security Intelligence Service

- FLQ

- Front de Liberation de Quebec

- IMVE

- Ideologically Motivated Violent Extremism

- Incel

- involuntary celibate

- MUU

- mixed, unstable or unclear

- PMVE

- Politically Motivated Violent Extremism

- RCMP

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- RMVE

- Religiously Motivated Violent Extremism

- UCR

- Uniform Crime Reporting

List of charts

- Chart 1: Police-reported hate crime in Canada, 2009 to 2024

- Chart 2: Police-reported hate crime in Canada by province and territory, 2017 to 2024

- Chart 3: Police-reported hate crime by offence type, 2024

- Chart 4: Rates of police-reported violent and non-violent hate crime in Canada, 2015 t

- Chart 5: Police-reported hate crime targeting religion, 2015 to 2024

- Chart 6: Police-reported hate crime by religion type, 2020 to 2024

- Chart 7: Police-reported hate crime motivated by race/ethnicity, 2015 to 2024

- Chart 8: Police-reported hate crime motivated by sexual orientation, 2015 to 2024

- Chart 9: Police-reported hate crime motivated by sex/gender, 2015 to 2024

List of figures

Hate crime: concepts/definitions

What is a hate crime?

Hate crime is a broad legal term that encompasses a diversity of motives, perpetrators, victims, behaviours and harms.

The Hate Crimes Task Force defines a hate crime as a criminal offence committed against a person or property that is motivated in whole or in part by bias, prejudice or hate based on race, national or ethnic origin, language, colour, religion, sex, age, mental or physical disability, sexual orientation or gender identity or expression, or on any similar factor. This definition has been endorsed by the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police (CACP) and adopted by the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey.

Hate crimes affect not only individual victims, but also the larger community. Hate crimes also have consequences that reach far beyond a specific incident and are particularly concerning because they:

- can have uniquely violent and assaultive characteristics

- cause trauma to victims, family, and friends

- can cause fear of being targeted for future crimes

- can escalate and prompt retaliation

- can foster community unrest

- threaten national values of tolerance and inclusion

It is important to note that while hate can be a motivator in these types of offences, it is often not the sole motivating factor. Research demonstrates that hate crimes are often motivated by multiple factors, including ignorance, fear, anger and social/political grievances (Janhevich, 2001; Tétrault, 2019; Thompson, Ismail and Couto, 2020), which can pose legal challenges for determining and demonstrating hateful motivation. In other words, in order to be convicted of a hate crime, it must first be proven in court that the offence was motivated fully or in part by hate.

Additional resource

Informational video series:

What is a hate incident?

Hate incidents involve the same characteristics as hate crimes but do not meet the legal threshold to be classified as criminal offences under Canada’s Criminal Code. In other words, hate incidents are non-criminal actions actions against a person or property that is motivated by bias, prejudice or hate based on race, national or ethnic origin, language, colour, religion, sex, age, mental or physical disability, sexual orientation or gender identity or expression or on any other similar factor. Examples of hate incidents include:

- sharing discriminatory material in person or posting it on the internet

- intimidating a person on social media because of their religion

- using racist slurs or epithets

- insulting someone based on their national or ethnic origin

- making offensive jokes about a person’s skin color or sexual orientation

Although hate incidents may not result in the laying of criminal charges, it is important that responding officers take these incidents seriously, and consider the impacts and harms caused to individuals and their communities. This includes the potential to generate fear in affected communities.

Providing a timely, compassionate and victim-centric response helps to mitigate the impacts of hate, reassure victims and their broader communities, and initiate the healing process.

Hate crime and the Criminal Code

Overview of applicable sections and general statutory aggravating factors

Hate crimes are criminal incidents that are found to have been motivated wholly or in part by hatred toward an individual or identifiable group. According to subsection 318(4) of the Criminal Code, identifiable groups are defined by colour, race, religion, national or ethnic origin, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or mental or physical disability. It is important to recognize that hate crimes and incidents may also be motivated wholly or in part by hatred toward an intersection of more than one of these identities.

There are several hate crime provisions within the Criminal Code:

- Advocating genocide (subsection 318(1))

- Public incitement of hatred (subsection 319(1)); wherein a subject wilfully promotes hatred against any identifiable group.

- Wilful promotion of hatred (subsection 319(2)); anyone who, by communicating statements other than in private conversation, wilfully promotes hatred against an identifiable group. The statement can be spoken, written or recorded and can include gestures, signs, photographs and drawings.

- Wilful promotion of antisemitism (subsection 319 (2.1))

- Conversion therapy offences (sections 320.101-104; subsection 273.3(1)); any form of treatment which attempts to actively change someone’s sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression.

- Mischief to religious property, educational institutions, etc. (subsection 430 (4.1)); for example, vandalizing a place of worship like a church, synagogue, a temple, gurdwara or mosque. Subparagraph 718.2(a)(i) of the Criminal Code allows for increased penalties when an offender is sentenced for any criminal offence when there is evidence that the offence was motivated solely or in part by hate. Simply put: any criminal act has the potential to be a hate/bias crime if the hate motivation can be proven.

- Relevant Criminal Code sections for each of these offences, along with general statutory aggravating factors, are reproduced below.

Attorney General (AG) Consent

There are procedural gateways to hate crime prosecution; under section 318(3) and 319(6) of the Criminal Code, consent of the provincial Attorney General must be obtained when pursuing charges for: Wilful promotion of hatred and Wilful promotion of antisemitism.

Laws pertaining to hate crime

Advocating Genocide

- 318(1)

- Everyone who advocates or promotes genocide is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not more than five years.

- 318(2)

-

In this section, “genocide” means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy in whole or in part any identifiable group, namely,

- killing members of the group; or

- deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction.

Public Incitement of Hatred

- 319(1)

-

Everyone who, by communicating statements in any public place, incites hatred against any identifiable group where such incitement is likely to lead to a breach of the peace is guilty of

- an indictable offence and is liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years; or

- an offence punishable on summary conviction.

Wilful Promotion of Hatred

- 319.2

-

Everyone who, by communicating statements, other than in private conversation, wilfully promotes hatred against any identifiable group is guilty of

- an indictable offence and is liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years; or

- an offence punishable on summary conviction.

Wilful Promotion of Antisemitism

- 319(2.1)

-

Everyone who, by communicating statements, other than in private conversation, wilfully promotes antisemitism by condoning, denying or downplaying the Holocaust

- is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years; or

- is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction.

Conversion Therapy

- 320.102

-

Everyone who knowingly causes another person to undergo conversion therapy – including by providing conversion therapy to that other person is

- guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than five years; or

- guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction.

Promoting or advertising

- 320.103

-

Everyone who knowingly promotes or advertises conversion therapy is

- guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than two years; or

- guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction.

Material benefit

- 320.104

-

Everyone who receives a financial or other material benefit, knowing that it is obtained or derived directly or indirectly from the provision of conversion therapy, is

- guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than two years; or

- guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction.

Removal of Child from Canada (for Conversion Therapy)

- 273.3(1)(c)

-

Removing from Canada a person who is ordinarily resident in Canada and who is under the age of 18 years, with the intention that an act be committed outside Canada that if it were committed in Canada would be an offence.

- guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than five years; or

- guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction.

Mischief to Religious Property, Educational Institutions, etc.

- 430(4.1)

-

Everyone who commits mischief in relation to property described in any of paragraphs (4.101)(a) to (d), if the commission of the mischief is motivated by bias, prejudice or hate based on colour, race, religion, national or ethnic origin, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression or mental or physical disability:

- is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years; or

- is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction.

Paragraphs (4.101) (a) to (d) indicate that property means:

- a building or structure, or part of a building or structure, that is primarily used for religious worship — including a church, mosque, synagogue or temple —, an object associated with religious worship located in or on the grounds of such a building or structure, or a cemetery;

- a building or structure, or part of a building or structure, that is primarily used by an identifiable group as defined in subsection 318(4) as an educational institution — including a school, daycare centre, college or university —, or an object associated with that institution located in or on the grounds of such a building or structure;

- a building or structure, or part of a building or structure, that is primarily used by an identifiable group as defined in subsection 318(4) for administrative, social, cultural or sports activities or events — including a town hall, community centre, playground or arena —, or an object associated with such an activity or event located in or on the grounds of such a building or structure; or

- a building or structure, or part of a building or structure, that is primarily used by an identifiable group as defined in subsection 318(4) as a residence for seniors or an object associated with that residence located in or on the grounds of such a building or structure.

Other Sentencing Principles

- 718.2

-

A court that imposes a sentence shall also take into consideration the following principles:

- a sentence should be increased or reduced to account for any relevant aggravating or mitigating circumstances relating to the offence or the offender, and, without limiting the generality of the foregoing,

- evidence that the offence was motivated by bias, prejudice or hate based on race, national or ethnic origin, language, colour, religion, sex, age, mental or physical disability, sexual orientation, or any other similar factor.

- a sentence should be increased or reduced to account for any relevant aggravating or mitigating circumstances relating to the offence or the offender, and, without limiting the generality of the foregoing,

Hate crime in Canada: patterns and trends

According to the Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, the following tables and charts explain various tendencies in hate crime offences over time. Additional data is available through Statistics Canada.

Hate crime is rising in Canada

As illustrated in Chart 1 below, between 2009 and 2024, levels of police-reported hate crime in Canada experienced some minor year to year fluctuation, followed by consistent and, at times, sharp year over year increases.

The first pronounced spike in hate crimes began in 2016 and coincided with the rise of populist politics and inflammatory rhetoric directed toward immigrant, racialized, and religious minority groups. Following slight declines between 2017 and 2018, hate crime rates have generally increased year over year. The number of police-reported hate crime nearly doubled between 2020-2024.

Chart 1: Police-reported hate crime in Canada, 2009 to 2024

Text version

| Year | Number of events |

|---|---|

| 2009 | 1,482 |

| 2010 | 1,401 |

| 2011 | 1,332 |

| 2012 | 1,414 |

| 2013 | 1,167 |

| 2014 | 1,295 |

| 2015 | 1,362 |

| 2016 | 1,409 |

| 2017 | 2,073 |

| 2018 | 1,817 |

| 2019 | 1,951 |

| 2020 | 2,646 |

| 2021 | 3,355 |

| 2022 | 3,612 |

| 2023 | 4,828 |

| 2024 | 4,882 |

Do levels of hate crime vary over time and space?

Yes. Although overall levels of police-reported hate crime have increased in Canada in recent years, there are distinct variations over time and at the provincial and territorial levels. As seen in Chart 2, these variations can be observed in the number of police-reported hate crimes in each province/territory between 2017 to 2024.

Chart 2: Police-reported hate crime in Canada by province and territory, 2017 to 2024

Text version

| Province or territory | Events per year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 2 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 17 | 19 | 29 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 19 | 16 | 21 | 18 |

| Nova Scotia | 21 | 32 | 32 | 58 | 70 | 115 | 194 | 164 |

| New Brunswick | 22 | 15 | 30 | 19 | 37 | 50 | 70 | 65 |

| Quebec | 489 | 379 | 399 | 454 | 486 | 419 | 729 | 723 |

| Ontario | 1,023 | 807 | 848 | 1,159 | 1,624 | 1,950 | 2,499 | 2,575 |

| Manitoba | 36 | 42 | 55 | 58 | 73 | 61 | 112 | 79 |

| Saskatchewan | 20 | 30 | 33 | 51 | 53 | 80 | 112 | 107 |

| Alberta | 192 | 245 | 207 | 294 | 339 | 319 | 370 | 398 |

| British Columbia | 255 | 259 | 321 | 519 | 612 | 545 | 674 | 692 |

| Yukon | 3 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 6 |

| Northwest Territories | 5 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 15 | 4 | 11 |

| Nunavut | 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 11 | 5 | 7 | 4 |

Though there is year-to-year fluctuation in the number of police-reported hate crimes across each of the provinces and territories, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nunavut, the Yukon, and the Northwest Territories have generally experienced the least number of hate crimes between 2017 and 2024, while British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec experienced comparatively higher numbers.

Where do hate crimes most commonly occur?

In Canada, between 2011 and 2020:

- 33% of police-reported violent hate crimes were committed in a park or field

- 2% of police-reported violent hate crimes were committed at a residence

- 18% of police-reported violent hate crimes were committed at a commercial business

In Canada, between 2011 and 2020:

- 30% of police-reported non-violent hate crimes were committed in an open area

- 24% of police-reported non-violent hate crimes were committed at a residence

- 14% of police-reported non-violent hate crimes were committed at an educational institution

- 13% of police-reported non-violent hate crimes were committed at a commercial business

Online hate crimes and incidents are also increasing. For example, the number of police-reported hate crimes that were classified as cyberhate more than doubled between 2018 and 2022 (from 92 in 2018 to 219 in 2022). As with any hate crime it is important to recognize that these figures underestimate the true number of cyberhate events, as most hate crimes go unreported.

The nature of hate crime victimization

In 2024, according to Statistics Canada:

- 55% of all hate crimes were non-violent.

- Mischief was the most frequent type of non-violent hate crime reported to police, representing 39% (1,889)

- 45% of all hate crimes were violent.

- Common assault (Assault, level 1) was the most frequent type of violent hate crime reported to police, representing 15% (741)

Chart 3: Police-reported hate crime by offence type, 2024

Text version

| Hate crime by offence type | Number of events |

|---|---|

| Homicide and related offences | 15 |

| Aggravated assault | 7 |

| Assault causing bodily harm | 342 |

| Assault, level 1 | 741 |

| Total robbery | 39 |

| Criminal harassment | 222 |

| Indecent harassing comms | 124 |

| Uttering threats | 601 |

| Other violent violations | 86 |

| Mischief | 1,889 |

| Hate-motivated property crime | 276 |

| Other non-violent offences | 182 |

| Public incitement of hatred | 125 |

| Other criminal code violations | 222 |

| Other violations | 11 |

As seen in Chart 4 below, while the number of violent and non-violent hate crimes generally increased between 2015 and 2024 (with some minor year-to-year fluctuation), non-violent hate crimes were statistically more prevalent.

Chart 4: Rates of police-reported violent and non-violent hate crime in Canada, 2015 to 2024

Text version

| Year | Events per year | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-violent | Violent | |

| 2015 | 785 | 487 |

| 2016 | 756 | 603 |

| 2017 | 1,272 | 796 |

| 2018 | 1,019 | 798 |

| 2019 | 1,086 | 865 |

| 2020 | 1,496 | 1,150 |

| 2021 | 1,881 | 1,474 |

| 2022 | 1,942 | 1,670 |

| 2023 | 2,632 | 2,196 |

| 2024 | 2,705 | 2,177 |

Additional resource

For an infographic on police-reported hate crime in Canada in 2021, please see:

- Infographic on police-reported hate crime in Canada in 2024 (Statistics Canada)

Hate crime victimization: targeted groups

Certain segments of the population continue to be disproportionately targeted for hate crimes and incidents. Provided below is an overview of common hate crime motivation types, segments of the population most likely to be targeted, and recent victimization trends across types.

Number of hate crimes per identifiable group targeted

Between 2020 and 2024, in those occurrences reported to police, the following identifiable groups were targeted:

- race/ethnicity (9,941)

- religion (4,871)

- sexual orientation (2,752)

- sex/gender (467)

- other motivations (797)*

* This category includes mental or physical disability, language, immigrants/newcomers to Canada, age and other factors – for example, occupation or political beliefs.

The following sections disaggregate hate crime motivation types to highlight trends over time and segments of the population that are disproportionately targeted.

Hate crime targeting religion

As seen in Chart 5 below, overall levels of police-reported hate crime targeting religion have fluctuated between 2020 and 2024, though the general trend over this period is upward, punctuated by spikes in 2017, 2021 and 2023.

Chart 5: Police-reported hate crime targeting religion, 2015 to 2024

Text version

| Year | Number of events |

|---|---|

| 2015 | 469 |

| 2016 | 460 |

| 2017 | 842 |

| 2018 | 657 |

| 2019 | 613 |

| 2020 | 530 |

| 2021 | 886 |

| 2022 | 768 |

| 2023 | 1,345 |

| 2024 | 1,342 |

Chart 6 below presents data on hate crimes reported to police between 2020 and 2024 by targeted religion type. Over this period, Canada’s:

- Jewish population experienced the highest levels of police-reported hate crime (3,229)

- Muslim population (784)

- Catholic population (360)

- population that indicated “Religion Not Specified” (463)

Chart 6: Chart 6: Police-reported hate crime by religion type, 2020 to 2024

Text version

| Religion | Number of events | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |||

| Jewish | 331 | 492 | 527 | 959 | 920 | ||

| Muslim | 84 | 142 | 109 | 220 | 229 | ||

| Catholic | 43 | 155 | 52 | 49 | 61 | ||

| Religion not specified | 72 | 97 | 80 | 105 | 109 | ||

The 2024 Annual Hate Crime Statistical Report issued by the Toronto Police Service reported an increase in hate crimes over the previous year, most often targeting the Jewish community. The report found that the Anti-Jewish mischief-related occurrences represent the highest, 33% (148 occurrences) of the total reported hate crimes in 2024.

Hate crime targeting race/ethnicity

Chart 7 represents data on hate crime reported to police, between 2015 and 2024, targeting race/ethnicity. In 2024, hate crime motivated by race/ethnicity accounted for 49% of all hate crimes reported to police in Canada.

Chart 7: Police-reported hate crime motivated by race/ethnicity, 2015 to 2024

Text version

| Year | Number of events |

|---|---|

| 2015 | 641 |

| 2016 | 666 |

| 2017 | 878 |

| 2018 | 793 |

| 2019 | 884 |

| 2020 | 1,619 |

| 2021 | 1,745 |

| 2022 | 2,002 |

| 2023 | 2,198 |

| 2024 | 2,377 |

Between 2020 and 2024,

- Canada’s Black population experienced the highest level of targeting by hate crime, totaling 3,859

- East or Southeast Asian population targeted in 1,078 hate crimes

- South Asian population targeted in 1,098 hate crimes

- Arab or West Asian population targeted in 1,060 hate crimes

- White population targeted in 400 hate crimes

- Indigenous peoples targeted in 352 hate crimes

- Populations from “Other” racial/ethnic backgrounds (Latin American, South American, and intersectional hate crimes that target more than one race or ethnic group; the target of 1,535 hate crimes)

Hate crime targeting sexual orientation

As demonstrated in Chart 8 below, between 2015 and 2024, police-reported hate crime targeting sexual orientation increased significantly spiking in 2023 with 889 reported crimes.

Chart 8: Police-reported hate crime motivated by sexual orientation, 2015 to 2024

Text version

| Year | Number of events |

|---|---|

| 2015 | 141 |

| 2016 | 176 |

| 2017 | 204 |

| 2018 | 186 |

| 2019 | 265 |

| 2020 | 258 |

| 2021 | 438 |

| 2022 | 509 |

| 2023 | 889 |

| 2024 | 658 |

Research shows that victims of hate crime targeted on the basis of their sexual orientation:

- tend to be young and male

- are three times more likely than other victims of hate to be subject to serious violence

In research conducted by Paterson, Walters and Hall (2023) on the impact of hate crimes and incidents on the 2SLGBTQIA+ community, they found that “Crimes motivated by hatred toward a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity typically cause greater physical and emotional harm than comparative crimes not motivated by hate.”

Hate crime targeting sex/gender

As demonstrated by Chart 9 below, hate crime targeting sex/gender increased steadily between 2015 and 2019, declined slightly in 2020, and then increased quite significantly through to the end of 2024. Noting that similarly to hate crimes targeting sexual orientation, hate crimes targeting sex/gender tend to involve violence. They also disproportionately target girls and women, and more often those from racialized and religious groups – most notably from Muslim and Indigenous communities – who tend to experience the highest levels of this victimization.

Chart 9: Police-reported hate crime motivated by sex/gender, 2015 to 2024

Text version

| Year | Number of events |

|---|---|

| 2015 | 12 |

| 2016 | 24 |

| 2017 | 32 |

| 2018 | 54 |

| 2019 | 56 |

| 2020 | 49 |

| 2021 | 60 |

| 2022 | 90 |

| 2023 | 129 |

| 2024 | 139 |

The Canadian Women’s Foundation provides information on The Facts about Gendered Digital Hate, Harassment, and Violence, reporting on women’s and gender-diverse people’s experiences with online and digital hate, abuse and harassment. It further highlights the role of intersectionality with women from racialized minorities, members of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community, the economically disadvantaged, religious minorities, disabled persons, and younger women, who are disproportionately targeted.

Other considerations of particular relevance to police

- Hate crimes are 54% more likely than other crimes to involve co-offending. Moreover, where hate crimes involve more than one accused, serious injury of the victim is 26% more likely to occur (Wang and Moreau, 2022). For more information on group offending, including hate crimes perpetrated by members of organized hate groups, see Hate groups in Canada.

- According to Statistics Canada (2023):

- Of the 2,872 people accused of at least one hate crime between 2012 and 2018, half (49%) had previously been accused in at least one police-reported incident (not necessarily a hate crime) in the three years preceding their first hate crime charge. More specifically, 32% were accused in one prior incident, 40% were accused in 2 to 5 prior incidents, and 28% were accused in 6+ prior incidents. Among all prior incidents, just over a quarter (28%) involved violence.

- Over half (54%) of the 2,872 people accused of a hate crime between 2012 and 2018 came into contact with police again (not necessarily hate-related) within 3 years of their initial hate crime charge. Of these, 27% were accused in one subsequent incident, 40% were accused in two to five subsequent incidents, and 33% were accused in six or more subsequent incidents. Among all subsequent incidents, 30% involved violence.

- Between 2018 and 2021, just over one in five (22%) of police-reported hate crimes resulted in charges laid; the vast majority of hate crimes over this period (69%) were not cleared because an accused person had not been identified. The remaining 9% were cleared in another way, such as by issuing a warning, caution, referral to a community program, or by the victim requesting that no further action be taken against the accused person. It is important to note that violent hate crimes (38%) were more likely to result in the laying or recommendation of charges than non-violent hate crimes (9%).

Hate groups in Canada

Two searchable databases of hate symbols, characters and themes exist to assist in their identification:

- The U.S. Anti-Defamation League (ADL): This may include some groups that are not currently active in Canada and/or may not include groups that are

- The Toronto Holocaust Museum's Online Hate Research and Education Project

What is a hate group?

The Anti-Defamation League refers to the term as an organization or group of individuals whose goals and activities attack or vilify an entire group of people on the basis of colour, race, religion, national or ethnic origin, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or mental or physical disability. The presence of racist or otherwise prejudiced members within a larger organization or group does not qualify it as a hate group; in order to be classified as such, the organization or group itself must be characterized by and promote a hate-based orientation or purpose. Further, the organization or group need not engage in criminal conduct to be labeled a hate group; as discussed below, some hate groups discourage the use of violence to advance their goals and beliefs (Southern Law Poverty Group, 2025).

How many active hate groups are there in Canada?

Estimating the number of active hate groups is a difficult endeavour; due to the often-volatile nature of hate group leaders and membership, such groups “start up, fracture and fold all the time” as a consequence of internal conflict. Further, some hate groups operate in the online space, others involve in-person interaction and still others are structured according to a hybrid online/offline approach. And finally, while some hate groups are highly and hierarchically organized, others are more loosely affiliated and splintered. Taken together, these factors make it difficult to track the number of hate groups currently active in Canada (Balgord and Smith, 2021).

Some researchers have, however, tried to estimate the number of hate groups in Canada, though estimates vary. Some research has suggested that, by the mid-2010s, there were more than 100 active organized hate groups in Canada (Amarasignam and Scrivens, 2017). By 2021, estimates ranged from 70-100 to approximately 300 such groups, though discrepancies across these more recent estimates are likely and largely a function of differences in the way researchers count hate groups. According to Lantz, Wenger and Mills (2022), there appears to be a general consensus that the number of hate groups in Canada has risen in recent years, likely as a consequence of:

- the rise of populist politics and the normalization of racist and incendiary political rhetoric that scapegoats racialized and religious minority groups for a host of community safety and national security issues.

- following the onset of COVID-19, widespread attributions of blame directed at people of Asian background prompted increased incidents of anti-Asian racism, discrimination and violence

- since its inception, Daesh-inspired attacks in North America and Europe have inspired hate crimes against Muslims around the world attacks in North America and Europe have inspired hate crimes against Muslims around the world

- successive migrant/refugee crises that expose asylum seekers and migrants to various forms of violence and harassment stemming from problematic narratives asserting that certain migrant and refugee groups are ‘cheating the asylum system’, ‘draining the welfare system’, and/or ‘stealing Canadian jobs’

Many of the groups stereotyped by these rhetorics have experienced significant spikes in hate crime victimization. In other words, hate crime victimization against certain segments of the population has been shown to increase in the wake of incendiary rhetoric that portrays them as threats to community safety and national security (Neidhardt and Butcher, 2022).

Hate crimes perpetrated in response to such attacks illustrate the relationship that sometimes exists between hate crime and violent extremism, wherein hate crimes are intended to serve as a form of vicarious retribution against innocent members of the broader Muslim community.

These and other events have served as a catalyst for people with particular worldviews to come together and mobilize against these and other perceived threats. The internet has facilitated such connections and provided a medium through which hate groups can instantly disseminate propaganda to a broad audience, recruit new members and organize protests and other group activities. It is this connectivity that makes transnational communication between hate groups possible; research shows that hate groups in one nation can and do learn from and inspire those in other nations, which can complicate enforcement efforts on the part of police and partner agencies (Aziz and Carvin, 2022; Hodge and Hallgrimsdottir, 2020).

In this broader context, hate groups in Canada appear to have grown in both size and number. Maintaining ‘traditional’ white culture and heritage is among the core goals of these groups, which are typically grounded in white supremacist ideology and espouse a host of beliefs including antisemitic and Islamophobic sentiment, though many groups also position themselves against immigrants, women, 2SLGBTQIA+ individuals and other racialized and religious minority groups(O’Donnell, 2020; Perry and Scrivens, 2018).

Do all hate groups perpetrate violence?

Though the vilification of groups of people on the basis of identity characteristics (such as gender, nationality, race/ethnicity or religion – or a combination of these characteristics) can inspire or be a precursor to violence, some hate groups do not endorse the use of violence, nor do they perpetrate violence in support of the organization or group’s broader goals. Research suggests that this may, in part, be a deliberate recruitment tactic; some groups have been purposefully de-emphasizing the promotion of violence and hate because it is off-putting to many and therefore not an effective means of ‘growing the movement’ (Southern Law Poverty Group, 2022; Tétrault, 2021). Others, however, do privilege and approve of the use of violence. Such varied orientations toward the promotion of violence can make it difficult to assess and/or identify potential threats and work to reduce the risk of hate-inspired attacks (note that such attacks may involve a spectrum of victim types – from individuals or small group targets through to mass casualty events). Though some hate groups do indeed perpetrate hate crimes, research shows that most hate crimes are committed by individuals with no affiliation to an organized hate group (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, 2020; Balgord and Smith, 2021).

Why do people join hate groups?

Research suggests that people join hate groups for a host of reasons, including but not limited to holding hateful views about certain segments of the population (Jayson, 2017; Schweppe and Perry, 2021). More specifically, people join hate groups due to:

- feelings of alienation and powerlessness

- feelings of loneliness; a desire for friendship and a sense of belonging

- a search for meaning and identity

- fear of those that are different and/or fear that one’s social group is ‘under threat’ due to immigration and demographic change

- anger and frustration

- a need to reaffirm a sense of dominance and privilege

- a tendency toward rigid ‘black and white’ thinking (that is, lack of critical thinking capacity)

- traumatic childhood experiences (American research found that 45% of former hate group members reported being the victim of childhood physical abuse, while 20% reported being the victim of childhood sexual abuse)

- family disruption in childhood, including divorce, parental incarceration or substance abuse on the part of one or both parents

A journalistic investigation by CBC News highlighted the presence of ‘Active clubs in Canada’ and some of the public places or businesses where they have been observed to gather, often using community locations to stage recruitment videos and to conduct warfare training.

In short, hate groups are thought to offer members a sense of identity, meaning and personal significance based on their affiliation with the group. Research shows that hate groups remain “overwhelmingly white and male”. The number of female members is comparatively smaller, with women performing a variety of active roles, including recruitment, gathering intelligence, disseminating propaganda materials, and direct participation in perpetrating violence, albeit at lower levels than their male counterparts (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2019). In recent years, some hate groups in the United States and Canada have actively recruited members from racialized groups in an attempt to soften their public image and bolster recruitment. (German and Navarro, 2023). People who join hate groups now come from all socioeconomic backgrounds, professions, and appear to be increasingly racially/ethnically diverse.

Information about Canadian hate groups remains fragmented and incomplete, which complicates efforts to generate a more fulsome understanding of the threat environment. Until this information has been systematically collated, officers interested in gaining a better understanding of active hate groups in their area of jurisdiction should contact the area within their service that houses this information.

Additional resource

The Organization for the Prevention of Violence has published Hate in Canada: A short guide to far-right extremist movements (2022).

Hate speech and freedom of expression in Canada

What is hate speech?

There is currently no universal definition of hate speech under international human rights law; the concept remains the subject of debate among scholars and practitioners.

To provide a unified framework to address the problem of hate speech on a global scale, the United Nations Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech defines hate speech as:

Any kind of communication in speech, writing or behaviour, that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of who they are, in other words, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, colour, gender or other identity factor.

Though not a legal definition, the UN’s conceptualization of hate speech includes three core elements:

- Hate speech can be conveyed through any form of expression, including images, cartoons, memes, objects, gestures and symbols and it can be disseminated offline or online

- Hate speech is “discriminatory” (biased, bigoted or intolerant) or “pejorative” (prejudiced, contemptuous or demeaning) of an individual or group

- Hate speech calls out real or perceived “identity factors” of an individual or a group, including: religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, colour, descent, gender, but also characteristics such as language, economic or social origin, disability, health status, or sexual orientation, among others

Examples of hate speech

It is important to note that hate speech can only be directed at individuals or groups of individuals, not against religions, ideas, philosophies, political parties, or states/nations and their associated offices, symbols or public officials.

The B.C.’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner’s website provides a few examples of what hate speech typically includes:

- describing group members as animals, subhuman or genetically inferior

- suggesting group members are behind a conspiracy to gain control by plotting to destroy western civilization

- denying, minimizing or celebrating past persecution or tragedies that happened to group members

- labeling group members as child abusers, pedophiles or criminals who prey on children

- blaming group members for problems like crime and disease

- calling group members liars, cheats, criminals or any other term meant to provoke a strong reaction

Freedom of expression and existing limitations

“This is a free country, I can say whatever I want.” To some extent – that’s true. The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (hereafter “the Charter”) outlines the civil and human rights that Canadian citizens, permanent residents and newcomers to Canada are guaranteed.

One of those rights is freedom of speech, which is laid out in paragraph 2(b) of the Charter and enshrines the fundamental freedom of “thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication.”

What this means is that those who wish to peacefully protest or convey a point of view have the right to do so, even if their viewpoints are considered offensive by others. However, these freedoms are not absolute; section 1 of the Charter states: “The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.

” In other words, there are limits to the kinds of offensive things that people can legally say.

For example, in a particular case from Toronto, an individual was charged with 29 crimes deemed to have been motivated by hate, including Advocating Genocide and Public Incitement of Hatred for allegedly posting statements online encouraging attacks on the Jewish community.

In addition, the Supreme Court of Canada has upheld restrictions on forms of expression deemed contrary to the spirit of the Charter. More specifically, an expression (which can be verbal or written) that incites hatred against any identifiable group where such incitement is likely to to contravene the Criminal Code and may therefore lead to the laying of criminal charges.

Hate crimes and incidents: victim/community reporting and why it matters

Why some victims choose not to report

There are several contributing factors involved in an individual’s decision not to report. A report by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights outlines these factors (which are not limited to):

- confusion/lack of knowledge about what is a hate crime/incident

- not knowing where or how to report it to police

- fear of escalation and/or retaliation

- embarrassment, humiliation or shame about being victimized

- previous negative experience with police, a lack of trust in police and/or skepticism about the police willingness or capacity to investigate these crimes

- normalization of hate victimization; research shows that members of marginalized groups often think that ‘everyday’ verbal abuse, online harassment, and other forms of targeted hostility are not serious enough to be reported to the police. Some even worry that they are wasting police time and resources or think that they have to deal with these issues by themselves

- for members of 2SLGBTQIA+ communities, fear of repercussions from ‘being outed’

- fear of jeopardizing immigration status

- a belief that the accused would not be convicted or adequately punished

- dealing with the hate crime/incident in another way

- concerns about not being taken seriously or not being believed

- cultural and language barriers

To further complicate matters, police officers’ varying levels of expertise in identifying crimes motivated by hate means that sometimes when victims do report such crimes to the police, they are not recognized or treated as such.

Why is it important that hate crimes and incidents be reported?

It is important that hate crimes and incidents be reported to and documented by the police for a number of reasons, including:

- unreported hate crimes and incidents cannot be investigated or (in the case of hate crimes) prosecuted, which means that accused persons are not held accountable and may be emboldened to re-offend

- victims who do not report hate crimes and incidents are generally not able to access the rights and resources entrenched in the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights

- hate crimes and incidents that are not reported are not officially counted, which obscures the true extent of the problem and the urgent need for action

- to ensure that operations are calibrated to the scope of the issue. Currently in Canada (as in other nations), hate crime units tend to be under-resourced, in part because reporting rates are generally low. This undermines police services’ capacity to respond effectively to hate crimes and incidents, support victims, offer reassurance to affected communities, and deploy proactive prevention-/intervention-based programs and initiatives.

The Canadian Race Relations Foundation developed A Toolkit for Communities that provides information on how to report hate crimes and incidents, and how community organizations can support persons targeted by hate.

How can police services work to increase hate crime detection and reporting?

The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2021) and Thompson, Ismail and Couto (2020) highlight that there have been increased efforts in recent years on the part of police services across Canada to facilitate the identification and reporting of hate motivated crimes and incidents, including:

- building institutional capacity: As of January 2019, 14 of the 20 largest municipal police services in Canada had dedicated hate crime officers and/or hate crime units

- demonstrating that police will respond swiftly and compassionately to all reported hate crimes and incidents

- maximizing cultural awareness to better communicate and work with individuals from diverse ethnic, racial and religious backgrounds

- increasing use of police training on hate crime and the importance of a victim-centred and trauma-informed police response; robust training can help officers to recognize and respond to hate crimes and incidents effectively. It is, however, important to note that many Canadian police services (particularly smaller services with fewer resources) have not yet developed, nor do they offer such training to their membership.

- developing innovative methods to encourage the reporting of hate, including a variety of community engagement, partnership and education initiatives, along with protocols that quell fears and reassure victimized communities in the wake of hate crimes and incidents

- working to counter discriminatory perceptions and practices in policing to improve relationships and trust with diverse communities and increase perceived police legitimacy

- publicly condemning hate crimes and incidents and articulating support for and solidarity with victims and their broader communities

- making data on hate crimes and incidents publicly available (publicly available data and reports signal that police acknowledge victims of hate crime and are committed to increasing transparency and raising awareness about the problem of hate, which can help increase public trust and improve reporting rates)

- engaging and supporting communities most vulnerable to hate crime victimization

- offering a variety of reporting approaches, including third-party and anonymous reporting options

Underreporting of hate crimes and incidents is a common occurrence across the country. Individuals may not want to report a hate crime or incident to police for a variety of reasons, including fear of retaliation, being desensitized to victimization or a mistrust of police. Continuing to engage in community outreach and education about hate crimes, the benefits of reporting, and the potential for early intervention is required to develop a fulsome understanding of the communities’ challenges in this space.

It is important to note that changes in reporting practices and the provision of additional support to victimized individuals and their communities can have effects on hate crime statistics. That is, higher rates of police-reported hate crime in certain jurisdictions may, in part, reflect differences or changes in the recognition, reporting and investigation of these incidents by police and community members. At the same time, increases in hate crimes and incidents may also reflect actual increases in the crimes and incidents themselves.

The impacts of hate on victims, communities and society

Background

Research shows that the impacts of hate crime can be profound, lasting, and more severe than for other victimization types. They also extend beyond those directly victimized, like a ripple effect, to affect members of the targeted group more generally (Pickles, 2020; Schweppe and Perry, 2021). Recognizing the impact of hate crimes therefore provides a basis for the respectful and sensitive treatment of victims, their families and communities, and can help first responders and victim services agencies better understand and meet their often complex needs. For more information on victim needs and services, please see Hate Crime Victim Support: A Critical Aspect of the Police Response and Types of Support Victims Need and Want.

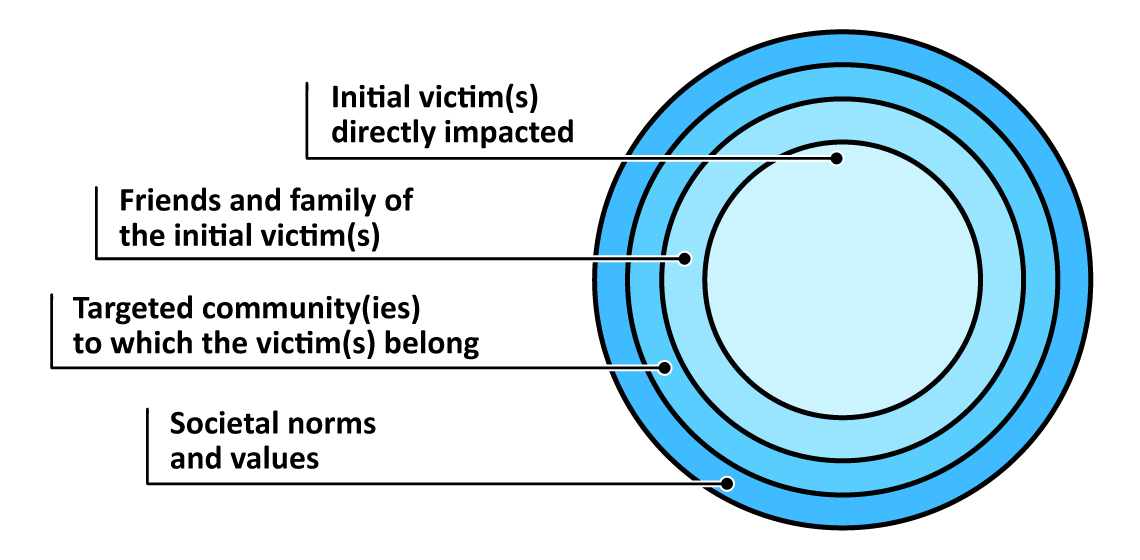

Figure 1 illustrates how hate crimes and incidents serve as ‘message crimes’ intended to intimidate and control, and the waves of harm that move beyond the victim(s) to also affect their friends and family members, communities (local, national, international and/or online) and, eventually, society (Iganski, 2001; Schweppe and Perry, 2021).

Figure 1: Waves of harm generated by hate crimes

Text version

Four concentric circles. Each circle represents a wave of harm. The primary wave is the central circle, labelled “Initial victim directly impacted”. The secondary wave in the next circle is labeled “Friends and family of the initial victim”. The tertiary wave in the next circle is labelled “Targeted community or communities to which the initial victim belongs”. The outermost circle is labeled “Societal norms and values”.

Sourced from: Schweppe and Perry, “A Continuum of Hate: Delimiting the Field of Hate Studies,” 510; Paul Iganski, “Hate Crimes Hurt More”, American Behavioral Scientist 45, No. 4 (2001): 629

The impacts of hate crimes and incidents

The impacts stemming from hate crime victimization are broad and can be influenced by a number of factors, including (but not limited to) previous victimization experience, the nature and characteristics of the hate crime or incident, the severity of the crime and injury, race/ethnicity, age, gender, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity, previous experiences with discrimination, and the availability of social support circles (friends, family, faith-based leaders, and others). The often intersectional nature of an individual’s identify can also serve to compound and intensify the harm experienced. It is therefore critical that police and partner agencies apply an intersectional lens when responding to hate crimes and incidents to ensure that the multiple biases that motivated the crime or incident are recognized (for example, hatred of race/ethnicity and gender identity) and the nuances of harm that stem from them are recognized and attended to (International Association of Chiefs of Police Response to Victims of Crime, 2018; Organization for Security Co-operation in Europe, 2020).

A CBC news story reported on the lived experience of an Edmonton high school student, where intersectionality of identities became a significant factor in their increased fear of victimization, even in the case where they themselves were not the victim.

Given the broad and diffuse nature of hate crime victimization, it is helpful to organize the impacts of hate according to whether an individual is directly or indirectly affected.

Direct impacts are experienced by the initial victim(s) of a hate crime or incident and can involve a variety of physical, psychological, emotional, financial, and social harms that can change over both the short and longer term. Indirect impacts, on the other hand, are ‘second-hand’ or ‘proxy’ harms experienced by individuals not directly affected by the hate crime or incident, including family, friends, witnesses, and community members.

Research shows that indirect impacts are often like direct impacts; simply knowing someone who has been victimized is often sufficient to cause these effects (Pickles, 2020).

Direct and indirect impacts of hate crime victimization may include:

- physical injury

- emotional and psychological distress

- trauma

- anger

- depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation

- long-term health effects including heart, liver, autoimmune, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- an extreme sense of isolation

- reduced sense of safety and security

- increased sense of vulnerability and fear of repeat victimization

- shame and humiliation

- being more security conscious and avoidant, which often involves the use of coping responses to avoid repeat victimization such as moving away, changing routines, avoiding people, places and situations perceived to be potentially dangerous, concealing aspects of their social identity (for example, by not holding hands with their same-sex partner in public, not wearing religious or cultural clothing or symbols)

- problems at school or work

- relationship problems with family and friends

- feelings of rejection and social exclusion that can trigger emotional and psychological pain and distress

- substance abuse and self-harm behaviours

- financial harms that stem from their victimization experience in terms of lost wages (due to injury and/or participating in the criminal justice process) and/or loss of/damage to property

It is important to recognize that first responders may also experience indirect impacts that stem from exposure to victims of hate. Vicarious trauma, sometimes also called “the cost of caring”, “compassion fatigue” and “secondary traumatic stress”, refers to the emotional, and psychological impacts experienced by those working in helping professions – such as police, other first responders and frontline social service practitioners – due to their exposure to victims of trauma and violence (Greinacher et al, 2019; International Association of Chiefs of Police, Enhancing Law Enforcement Response to Victims Strategy, 2018).

In addition to direct and indirect harms suffered by victims, their friends, families, and broader communities and responding frontline professionals, hate crimes and incidents also lead to broader societal impacts and harms. For example, if hate crimes are left unaddressed or are inappropriately/unprofessionally responded to, victims and their broader communities may lose trust in the criminal justice system and process. Hate crimes and incidents can also adversely affect the healthy and positive coexistence between different segments of a community. This can reduce levels of social cohesion and increase the likelihood of retaliation and civil unrest – all of which undermine human rights, the principles of equality and, by extension, important aspects of our democratic process (Müller and Schwarz, 2021; RAN Health, 2023).

Reimagining a path to support all Canadians: A review of services for victims of hate in Canada provides information on leading practices, challenges and opportunities with the current state of services for victims in Canada, offering recommendations for improved accessibility and effectiveness. (CRRF, 2022)

Victimization, trauma and the importance of a victim-centred police response: fact sheet and glossary of terms

Background

Hate crime victims often experience more severe impacts than do victims of equivalent offences not motivated by hate. Community members who share the identity characteristics that made the victim(s) a target of hate are also negatively impacted by hate crime, as are those who witness the crime/incident (Mellgren, Andersson and Ivert, 2017).

Responding officers are often the first representatives of the criminal justice system that victims of crime encounter. As such, they have an important opportunity to secure the scene, stabilize the victim(s), and provide important information, assistance and access to supportive services that can help initiate the recovery process in the immediate aftermath of a crime.

Understanding the post-victimization impacts that hate crimes and incidents can have for victims, their families, and their broader communities is critical to the provision of informed, sensitive, and respectful service delivery, and can assist responding officers to identify and help begin to address victim needs.

This fact sheet provides a glossary of terms related to victimization, along with concepts and approaches to enhance the police response to victims of hate crimes and incidents and provides hyperlinks to additional information for those who wish to learn more.

Glossary of terms

Victim Rights in Canada

The Canadian Victims Bill of Rights entrenches the rights of victims into federal law, including the right to (reproduced from Office of the Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Crime):

- Information

- Victims have the right to receive information about the justice system, and about the services and programs available to them. Victims may also obtain specific information on the progress of the case, including information on the investigation, prosecution and sentencing of the person who harmed them.

- Protection

- Victims have the right to have their security and privacy considered at all stages of the criminal justice process, and to have reasonable and necessary protection from intimidation and retaliation. Victims also have the right to ask for a testimonial aid at court appearances.

- Participation

- Victims have the right to present victim impact statements and have them considered in court. Victims also have the right to express their views about decisions that affect their rights.

- Seek restitution

- Victims have the right to have the court consider making a restitution order and having an unpaid restitution order enforced through a civil court.

Additional resources

Victim

The Canadian Victims Bill of Rights defines a victim as “an individual who has suffered physical or emotional harm, property damage, or economic loss as a result of a crime”. This fact sheet refers to people affected by hate crime as victims in order to be consistent with common legal and practitioner terminology. However, it is important to recognize that the terms “survivor” and/or “victim-survivor” are sometimes preferred because each emphasizes strength, agency and resilience instead of focusing solely on an individual’s status as a victim of a criminal act.

Victim-Centred Approaches emphasize victim safety, rights, well-being, expressed needs and choices, while ensuring the empathetic and sensitive delivery of services and supports in a non-judgemental manner (Goodman, Tax and Mahamed, 2022).

Victim-centred approaches for responding to hate crime also emphasize the often-intersectional identities of victims of hate. The concept of intersectionality refers to the ways in which multiple identity characteristics (race, ethnicity, gender, religion, sexual orientation, etc.) intersect and interact to produce unique dynamics and experiences.

A Black woman, for example, is both Black and female, which subjects her to discrimination (and, potentially, hate crime victimization) on the basis of both her race and her gender. It is often not possible to disentangle her identity as a Black person from her identity as a woman, nor is it possible to isolate which of these identity characteristics prompted her victimization as both may likely play a contributing role (Crenshaw, 1991).

Applying an intersectional lens to hate crimes is important because doing so contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the victim’s experience, which is critical to ensure that services and supports are calibrated to specific and sometimes distinct victim’s needs (Perry, 2009). Officers should therefore ensure that they take all aspects of a victim’s identity into account when assessing, recording and responding to potential hate crimes and incidents.

Culturally-Responsive Approaches refer to the ability of an individual or organization to understand, learn from, and interact effectively with people of different cultures, including drawing on culturally based values, traditions, spiritual beliefs, customs, languages, and behaviors in the design and implementation of service delivery.

Cultural responsiveness “enables individuals and organizations to respond respectfully and effectively to people of all cultures, languages, classes, races, ethnic backgrounds, disabilities, religions, genders, sexual orientations, and other diversity factors in a manner that recognizes, affirms, and values their worth. Being culturally responsive requires having the ability to understand cultural differences, recognize potential biases, and look beyond differences to work productively with children, families, and communities whose cultural contexts are different from one’s own” (National Association of Social Workers, 2015).

Trauma

Individual trauma results from exposure to an event or a series of events that are emotionally disturbing and/or life-threatening. Trauma can have significant adverse effects on the individual’s mental, physical, social, emotional and/or spiritual well-being that, without intervention, may persist over time (Center for Health Care Strategies, What is Trauma, 2021). The effects of trauma can be mitigated and the healing process initiated via supportive friend and family relationships, community support, personal coping resources and strategies, and access to trauma-informed mental health treatment.

It is important to remember that there is broad variability in trauma-related symptoms across individuals and cultural communities. Police and victim support partner agencies should speak with victims about their support needs and preferences, and work to connect victims with appropriate, culturally responsive and trauma-informed local agencies.

Vicarious Trauma, sometimes also called “the cost of caring”, “compassion fatigue” and “secondary traumatic stress”, refers to the emotional and psychological impacts experienced by those working in helping professions – such as police, other first responders and frontline social service practitioners – due to their exposure to victims of trauma and violence (Greinacher et al, 2019; and, International Association of Chiefs of Police, Enhancing Law Enforcement Response to Victims, 2018).

Fortunately, vicarious trauma can be treated and symptoms alleviated with counselling and early intervention. Identifying and addressing symptoms as early as possible is key to protecting the mental health of officers in this high-stress helping profession and, in turn, enhancing the quality of service delivery to the community (Torchalla and Killoran, 2022). The American Psychological Association provides additional information on understanding and addressing vicarious trauma in first responders.

Trauma-Informed Approaches refers to the provision of services and supports with an understanding of the vulnerabilities and experiences of people who have experienced trauma. Such approaches place priority on restoring the victim’s feelings of safety, choice, and control.

Victims of hate crimes and incidents that report their victimization to the police place their trust in the criminal justice system when they are acutely vulnerable; the attitudes displayed by system players can sometimes serve to re-traumatize victims, which can exacerbate the harm experienced (Office of Justice Programs: Model Standards for Serving Victims and Survivors of Crime, 2023).

The Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights provides examples of ways in which representatives of the criminal justice system – including police – can potentially contribute to this re-traumatization include:

- a failure to recognize potential hate crimes and incidents due to a lack of awareness and training

- a lack of a response, or a response perceived by victims to be unhelpful or unprofessional

- attributing responsibility for the crime to victims (victim-blaming)

- minimizing the seriousness of a hate crime and/or trivializing the victim experience and harm(s) experienced

- denying the victim’s perspective in the assessment and evaluation of the crime and/or not taking bias motivation into consideration or dismissing it as irrelevant

- displaying negative or prejudicial attitudes toward the victim(s)

- expressing sympathy and understanding for the perpetrator

- lacking appropriate knowledge, experience and skills to recognize the significance of the victim’s identity (or intersecting aspects of their identity) for the victimization they experienced and the services and supports they require to recover

- a lack of consideration for victims’ needs and preferences, especially the need for information and access to appropriate victim services and supports

It is important that all professionals working with agencies that support victims of hate crime (including police and other criminal justice actors) recognize that their actions and attitudes can have critical impacts on hate crime victims.

Traditionally, the criminal justice system has focused on identifying, apprehending, prosecuting and holding offenders accountable for their behaviour; the needs of victims are often left unmet. By recognizing that victim-centric, trauma-informed and culturally responsive approaches are core elements of an effective victim response, responding officers can prioritize victims’ early access to information and supportive services, thereby initiating the recovery process.

Responding officers can take steps to mitigate the possibility of inadvertently re-traumatizing victims while working to ensure they provide victim-centred, trauma-informed, and culturally responsive service. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe published The Sensitive and Respectful Treatment of Hate Crime Victims that provides key considerations and effective communication practices to help mitigate the potential for re-victimization.

Hate crime victim support: a critical aspect of the police response and types of support victims need and want

Introduction

Victim support is an essential and often overlooked component of a comprehensive police response to hate crimes and incidents.

Traditionally, the criminal justice system has focused on identifying, apprehending, prosecuting and holding offenders accountable for their behaviour; the needs of victims are often unmet. The failure to understand victim needs and provide timely access to appropriate and adequate care can exacerbate the harm experienced. By contrast, the provision of meaningful assistance and support can have a profound impact on the recovery process, empower victims, increase trust and confidence in police, and facilitate cooperation with police and the criminal justice system to hold perpetrators accountable. So, too, does the provision of respectful and dignified treatment of victims, which should be the cornerstone of the police response.

Responding officers should adopt a victim-centred approach that focuses on ensuring the rights, safety, well-being and expressed needs and choices of victims when responding to hate crimes and incidents. Responding officers should also recognize that victims’ needs are diverse, complex and may change over time – which necessitates a continuum of care over the short– and longer-term involving a range of partner agencies with expertise, resources and services that many police services cannot provide on their own.

Seven critical needs of victims and recommendations for responding officers

Both the International Association of Chiefs of Police and the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights published reports highlighting the critical needs for victims of crime (IACP 2018; ODHIR, 2020). Crime victims require a continuum of support and services to heal. Working to meet the seven critical needs of victims outlined below can provide a foundation for victim-centered, trauma-informed practices. While victim needs vary, these seven categories highlight areas of focus for police, who play a principal role in ensuring victims’ needs are understood and addressed with compassion and respect for their dignity.

1. Personal safety and security

In the aftermath of a hate crime or incident, victims may feel profoundly unsafe and need to be reassured by responding officers that appropriate actions will be taken to support and protect them. Wherever possible, responding officers should:

- provide information about risk reduction and the likelihood of re-victimization

- recommend actions to take when experiencing intimidation and fears about future harm

Physical, emotional, and psychological safety are all important for victims in the aftermath of crime. Wherever possible, officers should:

- recognize that victims’ safety concerns may also extend to children, family members, friends and community members

- create an environment where victims feel safe reporting crimes and expressing their thoughts, fears, and needs

2. Individualized support

In the aftermath of a hate crime or incident, some victims will require support to deal with the immediate consequences and impacts. This can include a host of support services provided by a diverse array of local agencies. Though the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights entrenches a victim’s right to receive information about the services and programs available to them, opportunities for connecting victims with the help they need are often missed by police. Wherever possible, officers should:

- allow support persons chosen by victims to be present when possible. When this is not possible, explain why.

- speak with victims to learn about their support needs and preferences

- facilitate connections to local agencies and services that are in keeping with the victim’s expressed needs and choices for ongoing support and assistance

3. Information

Hate crime victims will need information about their rights, what to expect in terms of the investigatory process, and future points of contact as the investigation progresses. Wherever possible, officers should:

- provide victims’ rights information and guidance around exercising those rights. Provide information in multiple ways (for example, in conversation, through written material/brochures, on agencies’ websites).

- provide updates on the investigation. Notify victims when a case does not result in an arrest and prosecution. Explain why and how decisions are made, referencing the specific legal reasons where applicable (for example, because the incident did not meet the threshold for the laying of criminal charges).

4. Access to and assistance with the criminal justice process

Victims need opportunities to participate in criminal justice system processes. Wherever possible, officers should:

- ensure information on various stages of the criminal justice process and what to expect is provided to victims in languages used by community members (such as spoken languages, sign language, braille)

- keep victims informed about the progress of their case as it moves through the criminal justice system

5. Continuity

Victims encounter multiple professionals and processes in the criminal justice system. Wherever possible, officers should:

- collaborate with other criminal justice professionals, community agencies, and victim services providers

- understand the roles and responsibilities of other professionals

- use consistent language and victim-centered, trauma-informed and culturally responsive approaches

- facilitate supportive handoffs to other police, criminal justice and victim services professionals as cases progress

6. Voice

Crime victimization involves direct or threatened physical, emotional and other forms of harm because of actions taken by others. The response to crime also involves decisions and actions by others. It is important for victims to have a voice in the criminal justice system; victims want and need to be heard, understood, believed and taken seriously. Wherever possible, officers should:

- encourage victims to ask questions and listen to their concerns

- invite victims and victim services personnel to participate in case-related discussions

7. Justice

Many cases do not result in the arrest, prosecution, and sentencing of offenders. Procedural justice, which refers to the concept of fairness in the processes that resolve disputes and allocate resources, may be the only form of justice that some victims receive. Wherever possible, officers should:

- recognize that not all victims define justice the same way

- explain criminal justice system processes and how decisions are made

- complete thorough trauma-informed and offender-focused investigations

- do their part to hold offenders accountable

- ask victims for their input and views

Types of victim services

According to Justice Canada, victims require a range of support types, including:

System-based victim services

These are independent from police, courts and Crown attorneys. System-based services assist victims throughout their contact with the criminal justice system. Services may include (but are not limited to):

- provision of information, support, referrals

- short-term counselling

- court preparation and accompaniment

- victim impact statement preparation

- liaising with police, courts, Crown and corrections

Police-based victim services

These are usually offered following a victim’s first contact with police. While victim service agencies may be located in police divisions or detachments, they are not always staffed by police employees; many police-based victim services have a coordinator, civilian staff and trained volunteers. Services offered may include (but are not limited to):

- provision of information and referrals

- assistance and support

- court orientation

Court-based victim services

These provide support for victims or witnesses. Court-based victim services provide information, assistance and referrals to victims and witnesses with the goal of trying to make the court process less intimidating. Services may include (but are not limited to):

- court orientation, preparation and accompaniment

- updates on case progress

- coordination of meetings with Crown counsel

- assessment of the availability of a child victim/witness to testify

Community-based victim services

These provide direct services to victims, which may include (but are not limited to):

- emotional support

- practical assistance

- information

- court orientation

- referrals

Volunteers and non-governmental organizations

Many police-based and community-based victim services utilize trained volunteers to assist with their program delivery. These organizations can operate at local, provincial and national levels, and offer a diverse range of services and supports.

Victim support is an essential and often overlooked component of a comprehensive police response to hate crimes and incidents. Understanding and working to meet the critical needs of hate crime victims can help to uphold the rights enshrined in the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights, assist victims as they move through the criminal justice process and initiate victim recovery.

For more information

- The Office of the Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Crime released a study entitled: Strengthening Access to Justice for Victims of Hate Crimes in Canada (2024) highlighting structural gaps in the resources and knowledge available to support victims of hate crimes